How to help delegates retain information: evidence-based frameworks for training

Course quality is one of the most important metrics for training providers. Most invest in good trainers, well-designed courses and up-to-date content. Yet many still see the same frustrating pattern: delegates pass the course, but weeks later key knowledge has faded, behaviours haven’t changed, and refresher training becomes reactive.

Unfortunately, delivery quality alone does not guarantee retention.

This article looks at well-established learning frameworks that can help to improve retention, and what they mean in practice for training providers, particularly those delivering regulated, compliance-led or safety-critical training.

Before having a look into the frameworks, it’s worth reminding ourselves of a few things:

- People don’t retain information just because a session was engaging

- Learning styles are not always a reliable way to design training

- Passing an assessment does not equal long-term understanding

- Cramming works for short-term recall, but not safe application

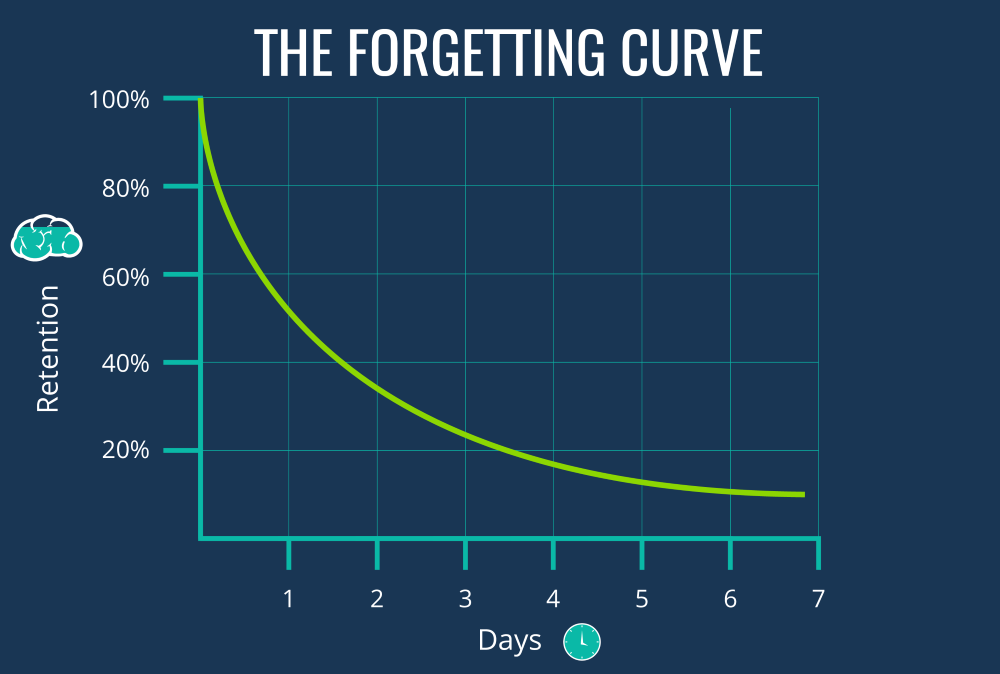

The forgetting curve: why most learning is lost quickly

One of the most uncomfortable ideas in learning science is also one of the most reliable: people forget new information rapidly if nothing reinforces it.

In training, this shows up all the time. A delegate completes a health and safety course, passes the assessment, receives a certificate, and then doesn’t revisit the material for years. By the time a refresher is required, much of the original knowledge has faded. This isn’t because the training was poor; it’s because memory decays without use or reinforcement.

So, what does this mean for training providers? If retention drops sharply after delivery, then the “event” model of training has limits. Courses that are treated as one-off interventions carry more risk, particularly when knowledge is safety-critical.

This reinforces the importance of post-course content and refresher training as part of the learning cycle itself.

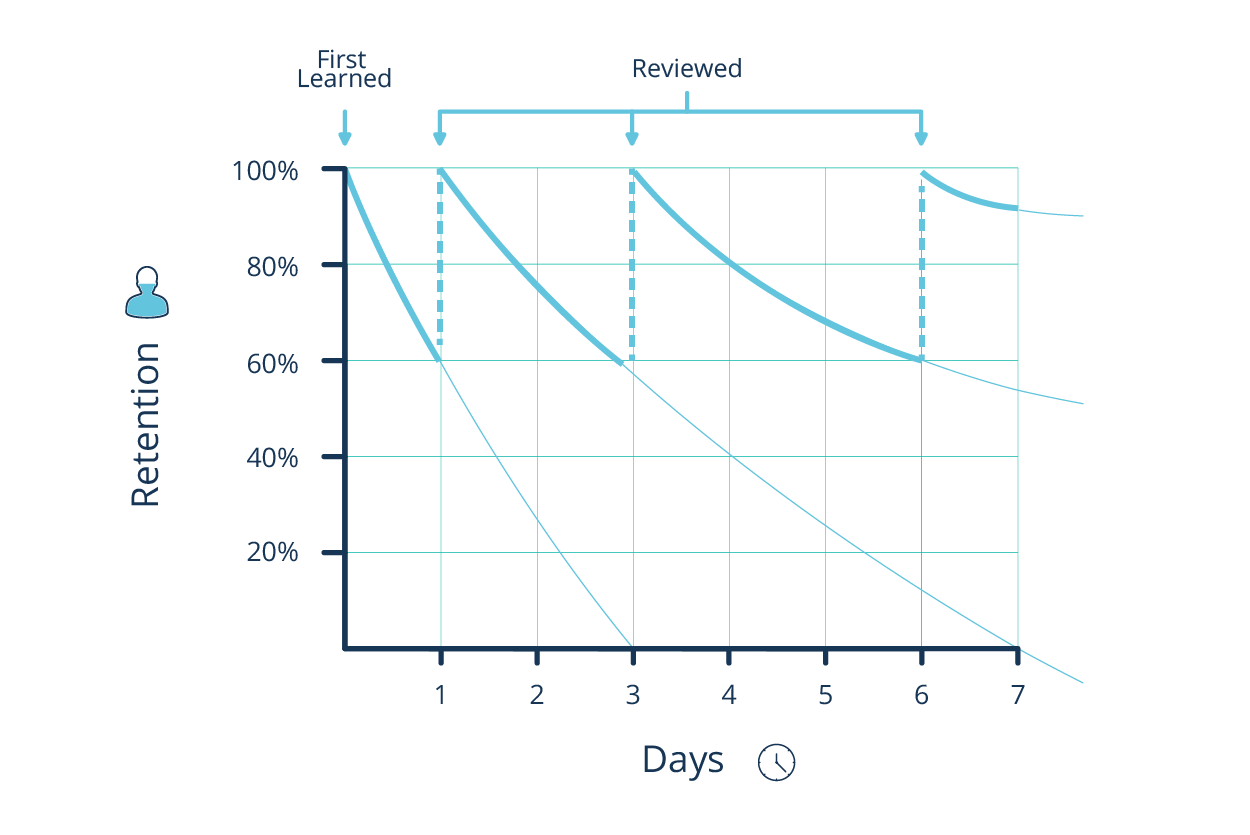

Spaced repetition: retention improves when learning is revisited

Spaced repetition builds directly on the forgetting curve. The idea is simple: information is remembered better when it’s revisited over time, rather than crammed into a single session. In practice, this means short, well-timed reinforcement moments.

Consider first aid or working at height training. Rather than relying on a full refresher every three years, providers can support retention through:

- Short reminder content sent weeks after training

- Scenario prompts that ask delegates how they’d respond in real situations

- Light-touch knowledge checks before requalification

The key point is that spacing strengthens memory, even when reinforcement is brief.

Active recall: why effort improves memory

One of the most counter-intuitive (and interesting) findings in learning research is that struggling to remember something helps fix it in memory.

Active recall means asking learners to retrieve information from memory, rather than re-reading or passively reviewing it. This feels harder, which is why it’s often avoided, but it’s far more effective.

Many courses rely heavily on classic content exposure; slides, handouts, and instructor explanation. Delegates initially feel confident because the material is familiar, but familiarity does not equal retention!

To put it into context, manual handling or fire safety training, active recall might look like:

- Asking delegates to explain steps without prompts

- Using short scenario questions rather than factual recall

- Following up with post-course questions that require explanation, not recognition

Assessment then becomes a memory-building tool, not just an evidence requirement for a pass/fail.

Kolb’s experiential learning cycle: experience alone isn’t enough

Experiential learning is often cited in training, particularly for practical or safety-based courses. But experience by itself doesn’t guarantee learning.

Kolb’s model highlights four stages:

Concrete experience

Learning starts with doing something real. A concrete experience is the moment the learner actually takes part in an activity rather than hearing about it second-hand. That could be attending a course, carrying out a task, observing a demonstration, or dealing with a real-world scenario.

In training, this is the practical element: operating equipment, completing a risk assessment, role-playing a difficult conversation, or walking through a site inspection. It’s where learning becomes tangible. The key point is that the learner isn’t passive. They’re involved, exposed to context, and often making small mistakes that create useful tension.

It goes without saying that for regulated training, this stage is essential. Delegates need to experience how those rules apply on site, under pressure, or with imperfect information. Without this stage, learning stays abstract and easy to forget.

Reflective observation (the stage that is most often skipped!)

Once the experience has happened, learning pauses. Reflective observation is about stepping back and thinking through what just took place. What went well? What didn’t? What felt difficult or unexpected? How did the learner respond, and why?

This reflection can be individual or shared. It might be a trainer-led discussion, a short written reflection, or a group debrief after a practical exercise. The important thing is that learners are encouraged to notice patterns and outcomes, not just whether they “passed” or “failed”.

In many courses, this stage is rushed or skipped entirely. That’s a missed opportunity. Reflection is where experience turns into insight. For example, a delegate might realise they followed a procedure correctly but struggled under time pressure, or that a small communication gap led to a bigger safety issue.

Abstract conceptualisation

Once the experience has happened, learning pauses. Reflective observation is about stepping back and thinking through what just took place. What went well? What didn’t? What felt difficult or unexpected? How did the learner respond, and why?

This reflection can be individual or shared. It might be a trainer-led discussion, a short written reflection, or a group debrief after a practical exercise. The important thing is that learners are encouraged to notice patterns and outcomes, not just whether they “passed” or “failed”.

In many courses, this stage is rushed or skipped entirely. That’s a missed opportunity. Reflection is where experience turns into insight. For example, a delegate might realise they followed a procedure correctly but struggled under time pressure, or that a small communication gap led to a bigger safety issue.

Active experimentation

Learning completes the cycle when learners take what they’ve understood and try it out again. Active experimentation is about applying new ideas, testing different approaches, and seeing what changes in practice.

This could mean repeating an exercise with adjustments, applying learning back in the workplace, or planning how they’ll handle a similar situation differently next time. It’s future-focused and practical.

In training delivery, this might look like scenario variations, follow-up tasks, workplace action plans, or re-assessment opportunities. Over time, learners build confidence because they’re not just absorbing information; they’re refining how they act.

For ongoing competence and compliance, this stage matters just as much as the first. It reinforces learning beyond the classroom and supports continuous improvement rather than one-off certification.

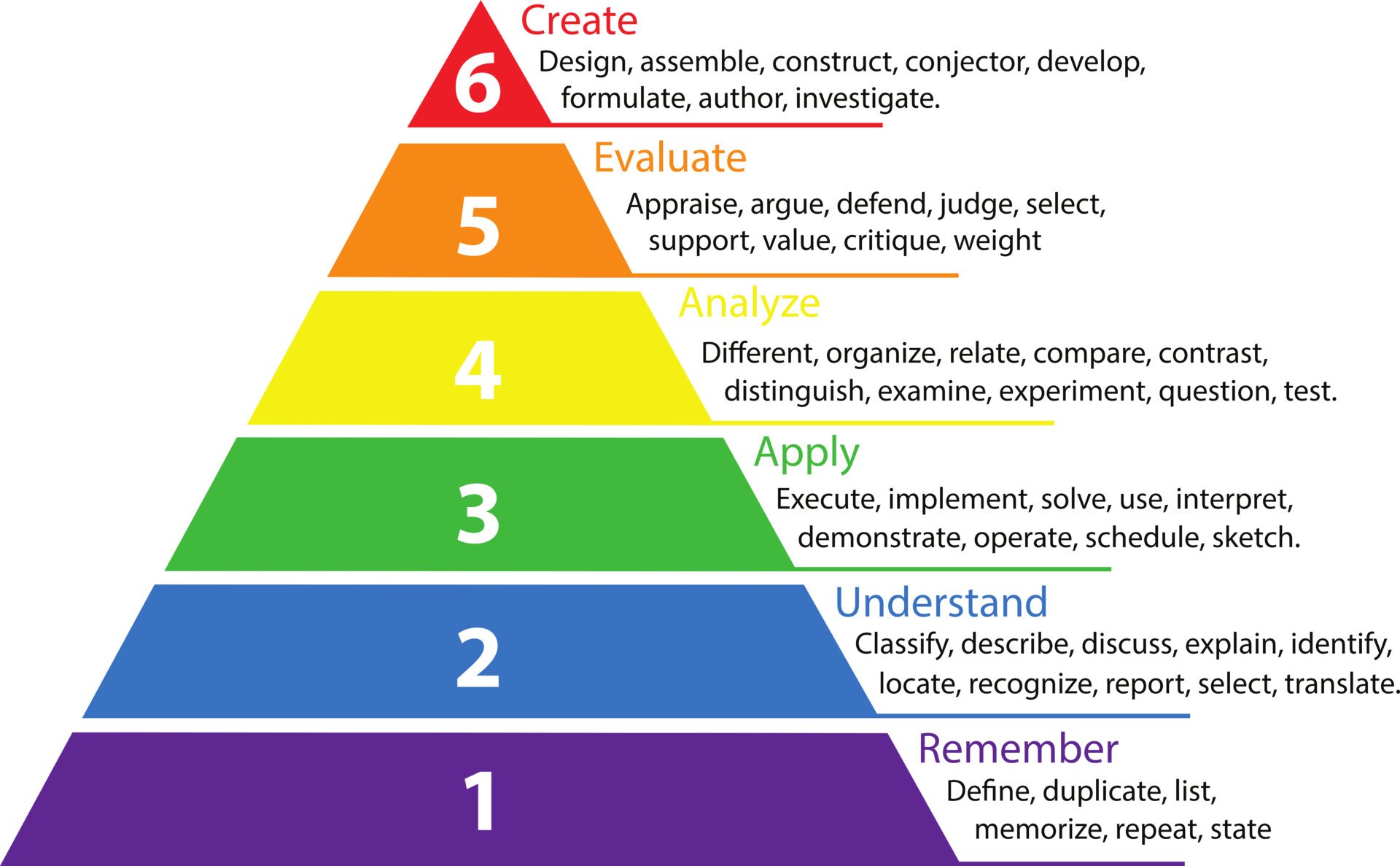

Bloom’s taxonomy: knowing isn’t the same as applying

Bloom’s taxonomy is simply a way of describing levels of learning. It was originally developed to help educators be clearer about what they wanted learners to be able to do at the end of a course, not just what content they wanted to cover.

At its simplest, it shows that learning isn’t one flat thing. There’s a progression:

At the lower levels, you’re dealing with knowledge and comprehension. This is where learners can recall facts, list steps, or explain a concept back to you. It’s important, but it’s also the easiest part to teach and assess.

As you move up, the focus shifts to using that knowledge. Applying means taking what you know and using it in a real situation. Analysing and evaluating go further again, asking learners to make judgements, spot risks, or choose between options. Creating sits at the top, where learners adapt or design solutions themselves.

The key idea is that being able to say the right thing doesn’t automatically mean someone can do the right thing. In training, that gap really matters. A delegate might pass a knowledge check with flying colours, but still struggle when the situation looks different to the example they were shown.

That’s why Bloom’s taxonomy is so useful. It helps training providers sanity-check their courses: are we just confirming people can remember information, or are we designing learning and assessment that reflects what they’ll actually need to do on site, under pressure, with imperfect information?

Take asbestos awareness training. A delegate might correctly recall legal duties, but retention only matters if they can:

- Recognise risk in unfamiliar environments

- Apply procedures when conditions aren’t textbook

- Make safe decisions under time pressure

This pushes providers to think carefully about learning outcomes and assessment methods, not just covering content.

Cognitive load theory: more content can reduce retention

There’s a natural temptation in training to include everything. After all, the stakes feel high. Cognitive load theory reminds us that working memory is limited. When learners are overloaded, retention drops, even if the information is important.

The theory breaks load into three rough types:

- Intrinsic load – the inherent difficulty of the subject itself. Some topics are just complex, and that can’t be fully removed.

- Extraneous load – unnecessary effort caused by how information is presented. Cluttered slides, poor structure, or too much detail too early all add here.

- Germane load – the mental effort that actually helps learning, like making sense of ideas or connecting them to real situations.

Good course design tries to reduce extraneous load so learners have enough capacity left for the things that really matter.

In practice, this is why “covering everything” can backfire. Even if all the information is relevant, presenting it at once forces learners to juggle too many ideas simultaneously. They may follow along in the moment, but little of it sticks.

For regulated training, cognitive load theory gives providers permission to prioritise. Core rules and principles land better when they’re taught clearly and cleanly, without being drowned out by edge cases and caveats. Context and exceptions still matter, but they’re far more effective when layered in later, once the fundamentals are secure.

That’s why this is usually a design problem, not a trainer problem. The goal is to structure learning in a way that respects how people actually process information.

What these frameworks have in common

Although these models come from different traditions, they point to the same conclusions:

- Retention is shaped over time, not in a single session

- Effortful learning beats passive exposure

- Reinforcement matters as much as delivery

- Operational follow-through affects learning outcomes

To conclude

When delegates fail to retain information, it’s tempting to blame attention, motivation, or the pressure of the day job. But the frameworks above point to a different conclusion: retention is largely shaped by how training is designed, reinforced and followed up.

In regulated training especially, the goal isn’t just knowledge transfer. It’s safe application over time. That means moving beyond the idea that learning happens in a single session, and accepting that reinforcement, recall and reflection are part of responsible delivery, not optional extras.

The good news is that none of this requires radical change or academic complexity. Small shifts, such as spacing learning, designing better recall moments, reducing overload, and building in reflection, can dramatically improve how much delegates actually take forward into the real world.

For training providers, improving retention isn’t about adding more content. It’s about being more intentional. When learning design and operational follow-through work together, retention improves naturally, and so do confidence, compliance and outcomes.

Want to stay up to date with what we're up to? Subscribe to our blog or follow us on Instagram!

..png?width=270&height=170&name=The%20hidden%20costs%20of%20training%20management%20(and%20how%20to%20fix%20them)..png)